Degrowth: a transformative approach to conserving biodiversity

The current global economic system, which is based on the extraction and exploitation of natural resources and the continual pursuit of growth, is at the heart of today’s joint climate and biodiversity crises (1). We cannot reasonably seek to address the devastating biodiversity loss we’ve witnessed around the world without also addressing this destructive system. By focussing on true indicators of human and planetary wellbeing—rather than growth—we can reorient our economies and societies around what matters most: a healthy, biodiverse natural world that can support both humans and wildlife. Degrowth provides a framework for this re-orientation, seeking to provide a good life for all within our planet’s biophysical limits.

Our natural world is in crisis; habitats are degrading, shrinking and disappearing, and the birds, fish, mammals, reptiles and insects that depend on them are losing safe places to live, and are themselves vanishing. Nature’s capacity to provide services that humans need to survive—like filtering air and water, providing healthy soils, and protecting us from storms—is quickly eroding. More than 75% of global food crops are at risk due to a loss of pollinators (1). And this is to say nothing of the psychological, spiritual and cultural benefits of biodiversity we’ll lose if this continues.

Figure 1 shows the relationships between different radiative forcings and global temperature increases, with the greenhouse gas line, in red, surpassing all others and causing the greatest increases in global heating. This illustrates what we have known for a long time—that humans are one of the main causes of climate change and the linked crisis of biodiversity loss. But what we now also know is that it is not humans, per se, but our growth-oriented economic system driving the destruction of our natural world. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) recently stated that ‘unsustainable production and consumption patterns in the G20 are driving the three environmental planetary crises: ‘the crisis of climate change, the crisis of nature and biodiversity loss, and the crisis of pollution and waste’ (2). Without addressing the root of these linked crises, we are unlikely to bring about sufficient change to halt or reverse them.

Figure 1. Global mean surface temperatures from Berkeley Earth (black dots) and modeled influence of different radiative forcings (colored lines), as well as the combination of all forcings (grey line) for the period from 1850 to 2017. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework recognises the need for ‘a transformation in our societies’ relationship with biodiversity,’ as well as ‘transformative action by Governments, and subnational and local authorities, with the involvement of all of society’ (3). What is unsaid here is the drastic shift that must occur within our societies and our economies—away from growth at all costs, and towards a holistic view of human and planetary health and wellbeing.

What is Degrowth?

Degrowth is both a movement and a concept, an idea—like freedom or equality—positioned to spur action and reform across a wide range of industries and sectors of society. Degrowth is not an aim in and of itself.

At the first international conference on socially sustainable economic degrowth for ecological sustainability in Paris in 2008, Degrowth was defined as ‘a voluntary transition towards a just, participatory, and ecologically sustainable society’ (4). On more straightforward, economic terms, sustainable degrowth is defined as an ‘equitable reduction (and eventual stabilisation) of society’s throughput’ (5). The key here, though, is that this intentional decrease of production and consumption should increase wellbeing for both people and planet, in the short and long term.

This is not a call for degrowth across the board and around the world, so it is important to specify degrowth where and degrowth of what. While it is true that as a global society, we are consuming and emitting far beyond what is sustainable, there is an enormous gap between the ecological footprints of the richest and poorest countries (6). So, while countries like the United States and the United Kingdom need to dramatically decrease material consumption, many countries across the global South still need to grow in order to reach levels of development required for physical wellbeing. In this sense, Degrowth proposes a redistribution of resources. It is helpful here to envision the doughnut proposed by Kate Raworth, depicted in Figure 2, where the inner ring represents minimum welfare requirements for all people, and the outer ring represents the environment’s ecological limits. The space between these concentric circles represents the ‘safe operating space’ for humanity (7).

Figure 2: The doughnut of social and planetary boundaries. Source: doughnuteconomics.org

While certain components of society will need to ‘degrow’—like the fossil fuel and other extractive industries, the size of our houses, the wealth of the top 1%, the use of cars, and the needless consumption of items that don’t really bring us happiness—many things can grow indefinitely. Knowledge sharing, cultural exchanges and social progress—things Herman Daly calls ‘moral growth’—need not have limits. Additionally, as society shifts away from private accumulations of wealth, governments can invest more in the things that serve all of society, and that genuinely contribute to wellbeing, such as healthcare, education, green space and other ‘commons’ (8).

How challenging the growth paradigm benefits global biodiversity

Economic growth is positively correlated with material consumption (6). As countries grow richer, they build more, buy more, do more, and all of this requires raw materials. This is a necessary relationship up to a certain point, so nations can build appropriate infrastructure, invest in healthcare, and reach levels of material consumption associated with prosperity. But as countries grow richer and richer and acquire goods far beyond their needs, their consumption of raw materials becomes unsustainable, the ecological cost of producing outweighs the benefit of consuming, and growth becomes ‘uneconomic’ (9).

As illustrated in Figure 3, our material footprint climbs ever higher as we pursue GDP growth, and this material footprint is unequivocally tied to habitat loss and fragmentation, which is the number one driver of species extinction and biodiversity decline around the world (1). To meet rich countries’ demands for production and consumption, we must clear land for animal agriculture, monocropping, timber, mining, and other exploitative and extractive practices. In so doing, we raze habitats to the ground. It is estimated that 60% of primate species are threatened by extinction from these very pursuits (10).

Figure 3. Global evolution of GDP and material footprint. Source: United Nations Environment Programme, World Bank.

Higher rates of economic growth are also linked to excessive emissions, from driving, taking airplanes, and heating and cooling our homes, in addition to the emissions from aforementioned material consumption. These planet-warming emissions have brought drastic changes to our climate, the effects of which are already playing out each year in every continent on the planet, from wildfires to floods and droughts to hurricanes. These extreme weather events destroy natural habitats of every kind and put thousands of species at risk (11). Furthermore, warmer temperatures are heating up the oceans, causing acidification and making many waters inhospitable for cold-water species. Global heating also upsets migration patterns for birds and alters growing cycles of certain plants, decreasing food sources for pollinators. Many species simply cannot adapt quickly enough to the rate our climate is changing.

A perhaps lesser-known issue tied to changes in biodiversity is the introduction of invasive species. In our world where economic activity is closely linked with fast-paced, international trade, ‘human-mediated species exchange’ is now one of the most common causes of species extinction (11).

Increases in consumption and trade are hallmarks of capitalist economic growth, which in turn lead to land use change, global heating and the introduction of invasive species. This is a human-made problem, with a human-made solution. We need to change the way we produce and consume, the way we accumulate wealth, and the way we live our lives.

And yet, many of us don’t want to do this, because it calls into question everything we know about the world today, everything we have been told is good and worth pursuing. Many of us don’t want to do this because it all sounds like less: less money, less clothing, less travel, less of the excess that those in the richest countries have come to rely on.

But what if it wasn’t less, at all?

Degrowth and wellbeing

The data is clear: Degrowth will bring about gains for biodiversity. But what about for people?

One key way to assess human welfare is by looking at life expectancy of a country, which is traditionally believed to positively correlate with GDP (12). The United States is one of the richest countries in the world and has a life expectancy of about 77 years. Yet there are plenty of countries with equal or higher life expectancies, and far lower per capita GDP; a by-no-means exhaustive list includes Japan, Italy, Cyprus, Chile, Netherlands, Greece, Bahrain, Estonia, South Korea, Panama, Spain, Thailand, Slovenia, Cuba, New Zealand and China. Costa Ricans live half a year longer than the average American, but do so with a per capita GDP about a quarter that of the US (13).

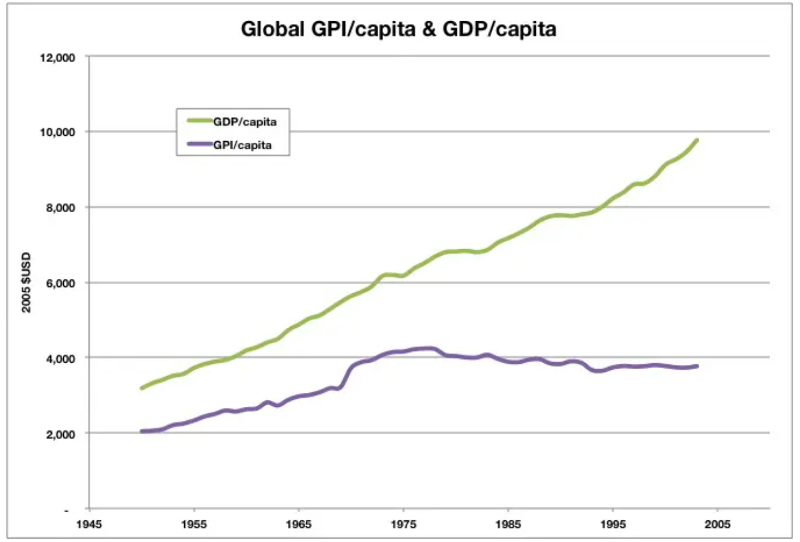

A better (though still imperfect) metric is the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), a version of the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare introduced by Herman Daly in 1989. GPI is meant to reflect economic welfare, rather than just economic activity, and adjusts for environmental costs and other negative externalities that are completely invisible in GDP—like crime and pollution—while including societal benefits like volunteering and care work. Comparing GDP and GPI over time, as depicted in Figure 4, illustrates how much of the picture is missed when we look at economic growth alone.

Figure 4. Global GDP per capita vs. GPI from 1945 to 2005. Source: Ida Kubiszewski et al, "Beyond GDP: Measuring and Achieving Global Genuine Progress," Ecological Ecomomics, 93, (2013).

Certain primary social goals like nutrition, access to energy, and sanitation are closely tied to resource use (14), which is why GDP and life expectancy (as well as other wellbeing indicators) rise in tandem at the early stages of development. Most countries can reach these levels of development with as little as $8,000 per capita GDP, while remaining within or near planetary boundaries. Secondary social goals associated with living a good life such as democracy, equality and social support are not tightly coupled to resource use (14), and can be achieved through more equitable distribution of wealth, community engagement, deliberative democratic processes, and investment in common pool resources.

The upshot is that we can liberate ourselves from the imperative of economic growth, directly benefitting biodiversity and the environment, and still provide citizens with long, meaningful lives.

Degrowth societies are also more equal ones, where wealth is distributed fairly and more people have access to public goods. Other aspects of post-growth societies are shorter working weeks and a universal basic income, both of which allow for people to focus on things they enjoy, while encouraging a more equal share of domestic duties. Women and other sectors of society who usually participate in free or underpaid care work can benefit greatly from such policies. Unsurprisingly, people living in more egalitarian societies report feeling happier than those in unequal societies (6); what’s more, they boast greater levels of trust, cooperation and social cohesion, as well as lower incidences of obesity and mental illness (15).

Bringing Degrowth to the people

Reorienting our economies around something other than economic growth is a massive shift, but we are an adaptable species. It wasn’t long ago that we asked the entire world to stop so together we could overcome Coronavirus. The biodiversity crisis we face today is a far greater threat than COVID-19, and yet we don’t ask much of people at all. Around 80 years ago, the United States asked everyone to pitch into the war effort, sacrificing cloth, metal and food to fight fascism in Europe. People came together like never before, bolstered by the knowledge that they were fighting a common enemy. We must once again come together, this time to fight overconsumption and wasteful practices for the common goal of biodiversity conservation.

Without even implementing specific conservation policies, Degrowth can have a positive impact on biodiversity and the natural world. If high-income countries reduced their ecological footprint to even that of upper-middle-income countries, we could reduce the global material footprint by billions of tons per year (6), and in so doing free up land for carbon-storing trees, grasses and flowers, and the wildlife that depend on them. We could allow habitats to regenerate and leave alone the ones we haven’t already spoiled. We could restore fish stocks, let wetlands flourish, leave mountains intact, curtail pollution, and at least make a dent in the millions of tons of plastic that end up on our beaches and in our seas every year, robbing hundreds of marine species of a safe place to live. In as little as thirty years, we could see rich ecosystems bounce back, providing a home to the animals whose land was taken from them (6).

We could live in harmony with nature once again.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Otero I, Farrell KN, Pueyo S, Kallis G, Kehoe L, Haberl H, et al. Biodiversity policy beyond economic growth. Conserv Lett. 2020;13(4):e12713.

2. Díaz S, Settele J, Brondízio ES, Ngo HT, Agard J, Arneth A, et al. Pervasive human-driven decline of life on Earth points to the need for transformative change. Science. 2019 Dec 13;366(6471):eaax3100.

3. UNEP [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Apr 4]. The G20 is a global force for sustainability. Available from: http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/g20-global-force-sustainability

4. 15/4. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. UN Environ Program. 2022;(Convention on Biological Diversity).

5. Research & Degrowth. Degrowth Declaration of the Paris 2008 conference. J Clean Prod. 2010 Apr 1;18(6):523–4.

6. Kallis G. In defence of degrowth. Ecol Econ. 2011 Mar;70(5):873–80.

7. Jason Hickel. Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. Penguin Random House UK; 2020.

8. About Doughnut Economics | DEAL [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 4]. Available from: https://doughnuteconomics.org/about-doughnut-economics

9. Fioramonti L, Coscieme L, Costanza R, Kubiszewski I, Trebeck K, Wallis S, et al. Wellbeing economy: An effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecol Econ. 2022 Feb;192:107261.

10. Daly HE. Steady-State Economics: A New Paradigm. New Lit Hist. 1993;24(4):811–6.

11. Moranta J, Torres C, Murray I, Hidalgo M, Hinz H, Gouraguine A. Transcending capitalism growth strategies for biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol. 2022;36(2):e13821.

12. Büchs M, Koch M. Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures. 2019 Jan 1;105:155–65.

13. Our World in Data [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 5]. Life expectancy vs. GDP per capita. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/life-expectancy-vs-gdp-per-capita

14. O’Neill DW, Fanning AL, Lamb WF, Steinberger JK. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat Sustain. 2018 Feb 5;1(2):88–95.

15. Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE. The enemy between us: The psychological and social costs of inequality. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2017 Feb;47(1):11–24.